GROWING UP AN ARMY BRAT: THE SILENCE

/“Children should be seen and not heard,” my mother said sternly from one end of the dining room table while my father nodded solemn approval from the other. As the eldest of three children, I was used to these frequent admonitions and knew it was my job to set a good example. I sat up straight, shut my mouth, and made sure my lap held both my napkin and my left hand, but my brothers had a hard time keeping still. Just one foot jiggling would make my mother scowl and wag her manicured finger at the offender.

The ’50s and ’60s were an etiquette-sensitive time, when most officers’ families had a thick volume of Amy Vanderbilt or Emily Post guidelines gathering dust somewhere on a top shelf. My mother, an attractive perfectionist who dressed stylishly and preferred well-behaved children, read those books. She was a rural small-town girl thrust into military society after my father returned from captivity in the Korean War, and it was her job to be a good army wife.

In those days, and perhaps still, spouses were a career asset. Or not. My mother and her contemporaries studied their military wife handbook, which contained detailed instructions on everything from how to serve tea to where to place ashtrays, napkins, and salad forks. They wrote thank-you notes, volunteered on committees, and shushed their children. They wore hats and heels and white gloves at public functions, sat with legs crossed at the ankles, and spoke only when spoken to. I felt awful when I learned that my aunt, beloved by us for her humor and spunk, cost her military husband a promotion because she “talked too much.”

“The First Amendment gives me the right to free speech,” I tried announcing at the dinner table. I was taking civics at school, thank you very much, and I knew what I was talking about. Except that I did not. Only civilians could speak freely. My father was subject to the Uniform Code of Military Justice, which limits free speech and conduct. He could say nothing that would undermine discipline or bring discredit upon the armed forces. He could not demonstrate for peace or criticize Congress or the President, his commander-in-chief. And because my father was our family’s commander-in-chief, we couldn’t, either.

Silence became my best friend. I relied on it to avoid domestic turmoil. My father suffered from PTSD, and I never knew when speaking my truth, however quietly, might unleash a verbal tirade or errant fist. As a young teenager, I had been walking the dog when I was accosted in the dark basement of our apartment building by an older boy who had dated one of my friends. He slammed me into the concrete block wall, thrust his arm across my mouth so I couldn’t scream, and started to rip my shorts off. Fortunately, I maintained my grip on the leash, and the dog’s frantic jumping and snarling convinced the boy to abandon his plan.

By the time I reached our apartment four flights up, saliva had crusted on my lips and my legs were shaking. I couldn’t catch my breath, and my heart pounded as I went inside. My father was reading the Sunday paper, and my mother was frying bacon. I let the dog off the leash and strode to my room without saying a word. So many people have far worse stories; I dared not tell mine.

“To be a daughter inside the Fortress is to be a kind of hovering spook: a weightless creature without power, without presence, without context, whose color is camouflage and whose voice is unheard,” Mary Edwards Wertsch wrote in Military Brats: Legacies of Childhood Inside the Fortress. Devouring that book years ago, curled in my patio chair over a Fourth of July holiday, I began to understand how growing up an army brat had shaped my life in ways I had yet to explore. Perhaps the pervasive silence steered me toward traditional journalism, where my job was to document both sides of events, to be fair and impartial, to withhold bias, to tell everyone’s story but my own. Keeping my opinions to myself was easy; I had suppressed them for so long I hardly knew what they were.

Writing one’s own story is hard. For an army brat, it’s even harder. It means breaking the rules, fighting guilt, skulking by the family picture wall where the man in uniform gazes down. But how very important it is to penetrate that silence, to speak the truth that heals and sets us free.

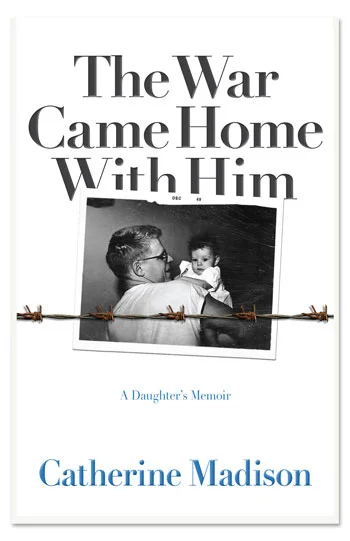

The author’s mother, wearing glasses and proper attire, at a public event.