GROWING UP AN ARMY BRAT: THE RULES

/By the time I was in the fourth grade, in 1959, I understood that my father was not like the rest of us. Of course he went off to work long days like most fathers, while we kids went to school and my mom took care of the house, but he was different in other ways. We wore clothes washed in a washer and hung on the clothesline to steam in the Texas heat, but he wore uniforms starched stiff and brought home in plastic bags. Every morning, he donned a fresh shirt never touched by my mother’s iron. He wore shoes spit-shined into black luster daily, while we wore dirty Keds until our baby toes fell out the holes on the sides. He wore a hat. We never did.

My father was in the army. The rest of us were, I thought then, civilians. We lived in a one-story house on a quiet San Antonio street with no sidewalks. We played games in the driveway and kickball on the lawn, where stiff spears of hardy grass sliced our feet if we went without shoes. We walked several blocks to the elementary school with friends whose fathers were not military.

Halfway through the fifth grade, everything changed. My father got orders to move to Germany, and apparently they were our orders, too. One page from a large stack of identical papers had to be handed to nearly everyone we encountered, from hotel desk clerks and ship stewards to cab drivers and military police.

“Don’t walk on the grass!” my father barked on our first day on the army post at Landstuhl. “Don’t walk on the grass!” I shouted to my brothers, then ages 5 and 3, often in the next weeks. This was a place of rules as circumscribed as the rows of apartment buildings we lived in, identical except for color, furnished with government-issue standards. Our families shared washing machines lining the basement and columns of clotheslines fronting the playground. We followed the rules posted in the stairwells. We were all in the army now.

What seemed strange at first quickly became routine: the MP saluting us through the gate, the segregation of officer and enlisted families, the expectations of cleanliness and order, the curfews. No one questioned these restrictions and rituals, at this or other posts where we later lived. Before the movie began at the theater, we stood with our hands over our hearts to sing “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Of course we all knew the words, and even the tone-deaf sang. At 5 p.m. everywhere on the post, traffic came to a halt. Everyone shut off their engines, got out of their cars, and saluted or covered their hearts while taps played. As the last bugle note drifted away, we climbed back in and went on.

Although I never heard it discussed, I suspect most of us, no matter what age, saw this regimentation as a good thing, a balm to counter the chaos that surrounded us. We lived in Germany during the days of the Cold War, when families more careful than ours made practice runs to the west coast of France to map an escape route if war broke out. We wore our dog tags, just in case. We lacked many things that Americans back in the States took for granted: real pasteurized milk in cartons, two-stick Popsicles, Levis available in all sizes, TV choices in English beyond “Bonanza” on Sunday evenings. Most of us didn’t have TVs at all, but we were army brats. We had transistor radios, scooters, each other, and the comfort of rules.

For my 50th birthday, my mate and I visited what is now Joint Base Lewis McChord in Tacoma, Washington, where I was born. I had not been there since I was nine months old. After checking credentials, the MP saluted us through the gate. Just beyond, we spotted several men in uniform, on their knees, using screwdrivers to clear the cracks in the sidewalk. The sidewalks were clean, and no one was walking on the grass. I was home.

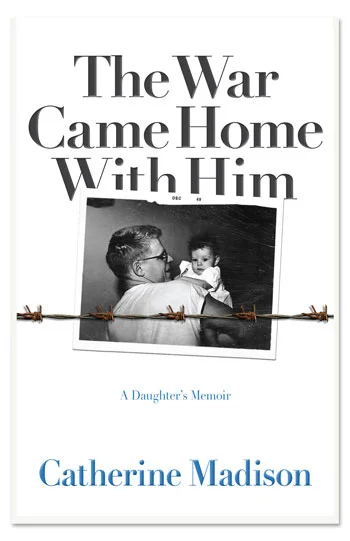

Our extended family in front of our quarters in Landstuhl, Germany, 1960. My father is wearing his hat. I'm on the left, dressed up in saddle shoes.